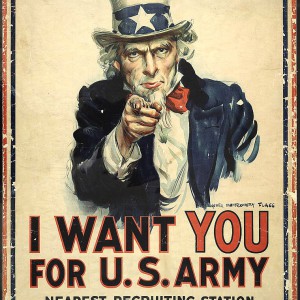

Call To Arms

It’s Veteran’s Day weekend, when we in the US honor those who have served in our Armed Forces. In this episode of BackStory, Ed, Joanne and Brian look at the many reasons for joining the US armed services – from a sense of patriotism, to escaping poverty, to earning American citizenship. They’ll discuss the struggles of the Continental Army to find enough soldiers during the Revolutionary War and how thousands of Filipinos became American citizens by enlisting in the US Navy after World War II.

View Full Episode Transcript

MALE SPEAKER: Major funding for BackStory is provided by an anonymous donor, the National Endowment for the Humanities, the University of Virginia, the Joseph and Robert Cornell Memorial Foundation, and the Arthur Vining Davis Foundations.

FEMALE SPEAKER: From the Virginia Foundation for the Humanities, this is BackStory.

ED: Welcome to BackStory, the show that explains the history behind today’s headlines. I’m Ed Ayers.

JOANNE: I’m Joanne Freeman.

BRIAN: And I’m Brian Balogh. Each week on podcast, Ed, Joanne, our colleague Nathan Connolly, and yours truly explore the history of a topic that’s been in the news. This week we’re marking Memorial Day, our national holiday that honors those who’ve died while serving in the military. So today, we’re going to look at some of the reasons people have enlisted in the US armed forces.

Let’s go back to the winter of 1781, that was the middle of the Revolutionary War. The conflict was in its sixth year, and things didn’t look good for the patriot cause. British troops had invaded Virginia, and burned Richmond. Historian Michael McDonnell says that by this point, Patriots struggled to find colonists who were willing to enlist, or even to keep fighting.

MICHAEL MCDONNELL: There Is a real problem of morale. So even as the British were invading, in some places in the state, people were rioting against their own local officials, and saying, we’ve had enough.

BRIAN: Virginia and other states tried to enforce conscription, but as the war ground on, McDonnell says, many colonists simply refused. Thousands of young men had already either served their time in the Continental Army, or had fought with local militias against the British.

MICHAEL MCDONNELL: There were many, many people who were, by this point, tired of the demands of the war. The initial flush of enthusiasm had worn off. And of course for a lot of people, who would have been just as happy to have stayed within the British Empire. Increasingly, during the war years, and it really comes to a head in Virginia. Particularly in the midst of the British invasion, there were uprisings, riots, rebellions in counties, in places like Virginia and elsewhere against conscription.

MICHAEL BLAAKMAN: The enlistment has become really a massive problem.

BRIAN: This is historian Michael Blaakman, he says state governments and the Continental Congress scramble to find a solution. They began to roll out more enticing incentives to attract soldiers.

MICHAEL BLAAKMAN: Whether it’s offering people higher pay, some states start thinking about offering slaves as forms of payment.

BRIAN: Blaakman says the Continental Army’s regular inducements, money, food, and shelter, just weren’t enough.

MICHAEL BLAAKMAN: These governments are terribly short on all kinds of material. They’re short on munitions, they’re short on uniforms, they’re super short on money, but land seems abundant, land seems almost infinite.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

ED: Yeah, you heard that right– land. States and Congress began to hand out land bounties. These were essentially IOUs that offered soldiers parcels of land in Western Pennsylvania and Ohio, in exchange for military service. Of course, this land wasn’t vacant. It had been occupied for millennia by American Indians. Blaakman says the founders had been planning to seize this territory from those native populations anyway, and these bounties served multiple purposes.

MICHAEL BLAAKMAN: A land bounty system promises to, after the war, plant a bunch of battle hardened veterans on the frontier, right? They’ll bring their families with them, they’ll set up farms and build houses. And in doing so, they will assert US claims to these regions that are still heavily contested between the United States and native peoples, whose homelands these are.

ED: Blaakman says these land grants served another purpose, they kept the colonists from switching sides to the British, and that was a real threat.

MICHAEL BLAAKMAN: Loyalty during the American Revolution was paper thin. I mean you had people who might switch sides, from patriot to loyalist numerous times throughout the war, based on shifting momentum, based on their own personal circumstances. So one of the things that a land bounty does, is it binds a soldier’s loyalty to the patriot cause. It says, yeah, we’ll pay you with this promise to get land, but you only get that land if we win.

ED: Now as we all know, the patriots did win. But most of the promises of free land were broken. After the war, speculators bought up many of the land bounties from soldiers who needed cash. So, that hoped-for class of landholding veterans on the frontier never materialized. The land bounties didn’t even solve the Continental Army’s enlistment problems. Historian Michael McDonnell says that no one incentive would be adequate to attract enough soldiers to the patriot cause. And yet, over the course of the war, enough men found enough reasons to keep on fighting.

MICHAEL MCDONNELL: Often, economic reasons, often because the army or the armed services promises the kind of a future for people who may not be sure about what they want to do. And of course is patriotism always. And we often see that at the beginning of wars, that there’s a flush of enthusiasm and patriotism. And then as wars grind on, and become bloodier, and become a little bit more complicated, and there’s a lot more light shown on the issues around the war, then there’s a backlash. And there’s a rethinking of why and how people would get involved.

ED: The American Revolution is often portrayed as a straightforward conflict between American patriots and colonists loyal to the British. But McDonnell’s research presents a much more complicated picture, one in which soldiers had multiple motives for enlisting. That makes sense, the choice for citizens to serve, and possibly die for their country, is often the most consequential decision that one can make.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

JOANNE: So today on the show, we’re looking at the history of military enlistment. Focusing on the reasons individual men and women sign up. We’ll hear why young American men join militias, rather than the US Army in the 18th and early 19th century.

NATHAN CONNOLLY: We’ll also learn why the American military actively recruited Filipino soldiers to serve in the American Navy. And we’ll hear from our listeners about why they chose to enlist.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

BRIAN: But first, let’s turn to the early 19th century. The US military was small, and few American men wanted to sign up for life as a professional soldier. But many American men did serve in local militias.

ED: You know, serving in the militia, Brian, was not really an onerous kind of service. You just showed up a couple of times a year, did some marching probably some drinking, and it was a non-partisan effort. This is something that brought together all the men of a community.

JOANNE: But young men who wanted to join up, found a new option on the eve of the Civil War. American politics was increasingly polarized and violent. During the contentious election of 1860, a strange new military-style organization spread across the North. It’s members called themselves the Wide Awakes. Most Wide Awakes were in their teens and early 20s. Even if they were too young to vote, they were all staunch Republicans determined to elect Abraham Lincoln, and defeat the Democrats at the ballot box. They loved martial displays, and certainly looked like they were ready to rumble.

ED: Tens of thousands of Wide Awakes paraded through small towns and big cities across the North in 1860. They marched at night, moving through the streets in crisp military formation in shiny new uniforms. Historian Jon Grinspan told me that the Wide Awakes attracted a lot of attention, and provoked more than a little annoyance wherever they went.

JON GRINSPAN: We have to imagine it’s midnight, 2:00 in the morning, you’re on the cobblestone streets of New York City. And first, you probably smell them coming a mile away, because everyone in this procession has an oil burning torch that just stinks, like coal oil or turpentine. And then you hear the sound of hundreds of people marching down cobblestone streets.

[FOOTSTEPS]

These large groups of young men, in companies of a hundred, wearing black capes, shiny, shimmering black capes, and caps, militaristic caps, and holding these torches. It’s incredibly striking, they’re usually silent. They’re not even cheering, they’re just usually stirring, silent marchers. And it’s powerful in Manhattan, but you have to imagine, it’s even more powerful in a small town in Wisconsin, where you only see 100, 200 people. And then, all of a sudden, hearing 10,000 people marching down Main Street.

ED: 10,000?

JON GRINSPAN: Yeah. This is a massive movement. Americans in 1860 believe there are half a million Wide Awakes. I think it’s closer to 100,000, but this is a movement that is popular in every northern state, and in a couple parts of the upper South as well.

ED: Well, wide awake sounds kind of like woke today.

JON GRINSPAN: Right.

ED: People really being– people who had been asleep, or who had been unaware, now getting it. Is that what Wide Awake means?

JON GRINSPAN: I never thought of the woke thing, but it’s exactly the same idea. That people who had previously been sleeping, and slumbering, and not paying attention to society are suddenly alert. And it’s a great icon too, all their propaganda and symbols have an open eye on it. Their opponents point to it too and say the Wide Awakes need to go back to sleep, and organize a movement called the Chloroformers, who are supposed to put the Wide Awakes back to sleep. So everyone gets in on the metaphor.

ED: So what’s the deal with the capes?

JON GRINSPAN: They look cool. The capes symbolize militarism. In the 1850s and 1860s, there’s something going on called militia fever, in which Americans and people in Europe are won over to the appeal of military symbols. Not necessarily for going out and fighting wars, but for the way it symbolizes progress, and dynamism, and organization. The young men who are–

ED: And dressing up, apparently.

JON GRINSPAN: Yes, and dressing up, and making a big thing out of an event. It connects to what the Wide Awakes are all about, which is they’re young, northern Republicans, who feel in some ways that their masculinity has been threatened by slave power. And Southerners who they believe dominate the federal government, have been caning northern senators in the Senate. And so getting together and looking as tough, and as bad ass as they possibly can in these uniforms is no accident. They go to the militaristic symbols on purpose.

ED: So we see the allure of the cape. I mean, that goes without saying. And the torch, that’s awesome too, right? But once you get beyond that first thrill of the dressing up, what is it that’s motivating them?

JON GRINSPAN: It’s funny, they don’t even care about Lincoln that much. I mean they want him to be elected, and he’s their guy, but what they care about is the Republican Party. These are people who grew up– if you think, the average Wide Awake is 21 years old or so, they’ve grown up in an environment where they feel as if Northerners are being stepped all over and bullied by a southern minority.

Politics has failed this young generation, but militarism has been really successful. They’ve looked at the Mexican-American War, which happened in their childhood, added hundreds of thousands of miles of land to America. So they see militarism as really compelling, and politics as really weak. And so, what they want ideologically is to stand up for the North, stand up for the Republican Party, defeat the Democrats, especially locally. They really see local Democrats in their communities as the main villains in all this.

ED: Did everybody welcome the sight of these marching silent men in torches and capes?

JON GRINSPAN: No, a portion of the country is thrilled by the Wide Awakes, and sees them as Batman, sees them as these caped Avengers who are going to solve their country’s problems. And then another portion of the country, people living in the South, people who support the Democratic Party, see them as an ominous sign of what’s happening to the country and what’s happening to democracy. They look like a military threat, and they look like a permanent paramilitary organization that’s taking over a peaceful democracy. And is more threatening to the Union than anything else at the time, as far as people who hate the Wide Awakes are concerned.

ED: So we know that the Civil War follows on this with remarkable speed, are the wide awakes playing in to that? Are they helping to foment militarism, or are they just partaking of this play militia fever that you’re talking about? How would you parse that relationship?

JON GRINSPAN: I think it’s both. I think the Wide Awakes are a good example of the power of military symbols to enlist people in a movement and to terrify everyone else who’s not in that movement. That for those people who join the Wide Awakes, they’re not preparing for a civil war, they’re not preparing for violence, they’re not any more violent than the Democrats or the know-nothings or any other party at the time, or organization. They think it’s a compelling symbol to organize a movement around.

But for people– if you live in South Carolina or Texas, and all you do is you read newspapers about a paramilitary movement marching down the streets in Manhattan, and Philadelphia, and Chicago, it looks really ominous and really threatening. And they don’t do it intentionally, but it definitely helps set the stage for people in the South to interpret the election of Abe Lincoln as a bridge being crossed. And as a moment when abolitionists have seized control of the federal government, and are running a permanent militaristic campaign against your interests. So they really scare people, people they don’t know, and can’t communicate with that well.

ED: So even though they did not intend it, they were literally playing with fire. And not intending war to result from this, and everybody is surprised that despite this kind of behavior, that it does somehow eventuate in war. Do the Wide Awake membership eagerly rush into the army?

JON GRINSPAN: As far as we know, yes they do. And they also– individuals, who are Wide Awake organizers and activists, set up their own militias that become part of the Union Army. And actually, some of the first bloodshed of the Civil War in St. Louis, the fight at Camp Jackson, to get the arsenal away from the potentially secessionists, governor of the state, is organized by Wide Awakes. They’re German-American Wide Awakes who are organized from a political movement into a military movement. Which brings about a battle, I think 75 wounded and 28 dead. Some of the first bloodshed of the war is Wide Awakes.

ED: Do you think that the war fulfilled this longing that they had before, to prove their manhood?

JON GRINSPAN: Yeah, they’re volunteering excitedly, and the war– it seems like a great opportunity to live that out. I think most people who experience a war give up on that that romantic view of it pretty quickly. But in 1860, 1861, it seems very compelling, it seems like the future of the country. And for those people who hate the Wide Awakes too. For Southerners who enlist in the Confederate Army, they are just as compelled by the sense that they are defending their homeland from this invading force.

ED: Jon Grinspan is a curator of political history at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, and author of The Virgin Vote. Earlier, we heard from Michael McDonnell, a historian at the University of Sydney in Australia. And historian Michael Blaakman at the University of St. Thomas.

JOANNE: It’s time to take a short break. When we get back, just what did all those local militias actually do in the early republic? But first, a word from today’s sponsor.

JOANNE: We’re back talking about the history of enlistment in America.

BRIAN: Ed, I’m dying to hear about a phrase used in the interview, “militia fever,” but before I worry about the fever, I’d love to hear a bit more about militias in the early republic, Joanne.

JOANNE: Well, of course the militia, Brian, that’s a big American tradition that goes all the way back, even before the early republic, to colonial America. And even before that, back to England. It involves local men who must join if they’re between the age of 16 and 60, and basically they’re for local defense and safety.

Now that sounds really official and formal, but the fact of the matter is they didn’t meet very often, unless there was a threat. And sometimes Native Americans were a threat, and certainly the revolution is its own little period. Generally, they would meet maybe once or twice a year, just to sort of establish the fact that they were there.

ED: Kind of knock the rust off their guns.

JOANNE: Exactly. They had to put on– march around, actually. They got– I’m sure– a great deal of fun out and parading around the town green. And everyone came out and applauded, and sometimes they got to make a fake battle, and there was a heck of a lot of drinking. And really the militia did have the reputation of being a bunch of goofy guys who don’t know what they’re doing, and aren’t really good at handling rifles.

ED: In all honestly, they would have been. Right?

JOANNE: Yeah.

ED: Fighting requires incredible discipline and training, and these guys wouldn’t have had any. So I think the distance between the militia and the real army was enormous.

JOANNE: Well, first of all, the militias weren’t trained. You might not say they’re military units, they’re armed local people who are supposed to be there for defense. I mean in that tradition, that idea that local men will rise up and protect what’s theirs, that’s a sort of Jeffersonian yeoman farmer ideal as well. There were so many fears in the same time period of a standing army as a tool of despotism.

ED: Standing armies, we always say that. Why call it standing armies?

JOANNE: That’s true. Sitting armies.

BRIAN: Sitting armies are so ineffective, Ed. Before they invented tanks, sitting armies just don’t cut.

JOANNE: Running armies? No, it’s true. Standing army, permanent army, right? That would be a better way of putting it, a permanent army. But then the 19th century, Ed, I’m going to toss the ball to you now. So this tradition continues on for a while, what happens then when you get a little further into the 19th century?

ED: Well, for much of the 19th century, after some of the threats that you talk about recede, once the English are defeated in the Revolution, and once the American-Indians had been driven to the West, it’s hard to imagine much of a reason to get together and drill in the town square with your rusty muskets. But it goes from being a joke, to being in the 1850s quasi professional. In the sense that it becomes more like a military unit. The Wide Awakes are not alone in their uniforms, in they’re marching, in they’re gathering, in their discipline. And you’d find Northern and Southern militia are both doing this, enlisting men in even when there’s no crisis.

BRIAN: But, Ed, why do that instead of enlisting in the Army?

ED: Because to be a career Army officer is meant to be shipped off to some godforsaken obscure fort somewhere, where nothing is ever going to happen, and to dash your hopes for a good marriage, and to dash your hopes for a successful career. But you can be a young doctor, or lawyer, or carpenter, and join the militia, and have some of the excitement of the military-like experience without the dislocation that comes from actually joining the Army.

JOANNE: And the enforced discipline and the enforced time that you have to be there and everything else. All of the things that are cast in stone.

ED: It’s all the fun of the Army with none of the risk and costs.

BRIAN: So being all you can be, back in those days, entailed pursuing your private ambitions, and then showing up on occasion to demonstrate your manhood in cool looking gear.

JOANNE: And also, of course, in addition to showing your coolness, you are demonstrating civic awareness of some kind. Whether or not you’re feeling it, you’re definitely demonstrating it.

BRIAN: Yeah.

ED: So, Ed, Brian, I want to throw into the conversation something that we would associate with enlistment, but we haven’t really talked about it. And that’s patriotism.

ED: Oh yeah.

JOANNE: Certainly if you look back to the early period that I write about, local units, like the militia units, were also community things. Many people in colonial and even in early America conceived of their colony and then their state as their country. And they were fighting for their community, and in that sense, their country too. Patriotism was local, but it was no less meaningful or important to them. But that obviously has to change and grow over time.

ED: Well, it doesn’t change up until the eve of the Civil War, because Robert E. Lee famously says “I cannot raise a sword against my own people. I would be patriotic to Virginia, rather than be patriotic to the United States, to which I have sworn a lifetime oath.” But here’s the thing, when the enlistment for the Civil War begins, the militia in each community would go into this Army, both Northern and Southern, and then if they were decimated at a particular battle, that community would just be wiped out back home. All the young men of the place would be killed in a single charge. Right?

JOANNE: Wow.

ED: And so you have– the thing that was seen as its great strength, its ties to the local community, end up being something that was really just crippling to that same community when those young men went off and died. Now after the Civil War, people talk about the United States as a single entity rather than as a union of states. From then on, people are going to know what enlistment means. Enlistment means you’re signing up for a big national army, routinized, professionalized, that is a career, in a way that it was not before the Civil War.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

JOANNE: It’s time to take a short break. When we get back, listeners tell us why they enlisted in the armed forces. But first, this quick message.

JOANNE: OK, Ed. What do Dolly Parton, Don King, and Albert Einstein all have in common?

ED: Oh gosh, well, one thing they have in common is something I admire so much and try to embody in my own life, is pretty extravagant hair.

JOANNE: That is true, they all have signature hairstyles. Their locks say something about who they are. Now have you ever had some kind of a signature hairstyle, Ed?

ED: In the very early 70s, when I finally was allowed to have my hair the way that it was meant to be, which is out of control, and curly, and too long. It meant I was like Bob Dylan. And then while other people adapted to the times, I refused to, so I still look like that.

JOANNE: History forever, right, Ed? Historical hair.

ED: I’m letting my freak flag fly, except it won’t actually fly. It just kind of sits there.

JOANNE: Well, that leads us into the question that we’re going to be talking about soon. And that is, what does your hairstyle say about you? How does your hair convey your identity? Or are you happy that it doesn’t? So listeners, send us a 30-second voice memo from your smartphone to BackStory@Virignia.edu.

ED: And we’ll feature some of your stories on our upcoming episode on the history of hair.

JOANNE: We were just talking about the various reasons Americans enlisted in militias in the Colonial Era and Early Republic. But now we want to turn to your reasons for joining the military. Over the past few weeks, we’ve been asking our listeners to send us their enlistment stories. Here’s a sampling of those voices.

JASON CANE: Hey BackStory, my name is Jason Cane. I enlisted in the army after sleeping through my midterm exam for my evolutionary biology class in my senior year of college. I was an evolutionary biology major, I realized that I would never be able to go on and get a PhD. I needed some new discipline in my life, so I ran away to join the Army. 10 years later, I went through five combat deployments, went to grad school, and finished that goal. Anyway, last year I graduated from Harvard. So yeah, it all worked out, wouldn’t change a thing.

RUSSELL FINNEGAN: My name’s Russell Finnegan, I am an army captain, currently serving in Fort Bragg, North Carolina. I decided to join the Army, in large part, because of 9/11. It happened while I was in middle school, but had a really big impact on me. And I’d say to some measure or another, most people in my generation, who I serve with in the Army, and especially the generation mainly before me, there’s just so many guys I work with who came into the force because of 9/11, because of that impact.

RAYMOND CHRISTIAN: My name is Raymond “Ray” Christian. I joined the Army right out of high school at 17 years old in 1978. My primary motivation was to escape the only life I’d ever known. Growing up living in poverty and my goal was also to realize the life I dreamed of, the only realistic way I thought was available to me. I was a blue collar person with a blue collar background, and I wanted to earn some respect. And in my community, it wasn’t uncommon to see guys who returned right out of high school in their uniforms from different branches of the military. Or older guys would always say things like, yeah if I stayed in, I would have made something special out of myself. So I had that social community motivation for joining.

STEPHEN STACEY: Hey BackStory, my name is Captain Stacey. I’m a US Army physician, paratrooper, and flight surgeon. When I was in college, I knew I needed a way to pay for medical school, and I considered the Army as a way to do that. I also wanted to be motivated by a sense of patriotism, but at the time I just felt like I wasn’t patriotic enough to be a part of the Army. To help me get over that feeling, my recruiter brought in a Lieutenant Colonel who was also a physician. Her message to me was, it’s OK if it’s all about the money, you don’t need anything else, I joined for the money, plenty of people joined for the money, you can join for the money too. I took her advice, and I’m pleased to say that even though I joined for the money, I’ve developed a strong sense of patriotism and a love for the Army as I’ve served throughout Europe and the United States. Thanks BackStory.

BRIAN: Those were the voices of Jason Cane, Russell Finnegan, Raymond Christian, and Stephen Stacey. Thanks to all of you who reached out to share your stories.

BRIAN: For decades, enlistment in the military has been closely associated with American citizenship. In 1862, Congress passed legislation that offered naturalization for immigrants who enlisted in the US army during the Civil War. After World War I, the government declared that any immigrant fighting for US forces was eligible for citizenship. But we’d like to turn to a unique example in American history, when the US military actively recruited soldiers from a former colony.

JOANNE: The Philippines became a US protectorate after the Spanish-American War in 1898. The US occupied the island nation for almost 50 years, including through a bloody and failed uprising for self-rule. The Philippines finally gained its independence from the US in 1946. A year later, the two countries signed an agreement that allowed the United States to maintain a military presence in its former colony. The accord included an unusual provision, it allowed young Filipino men to enlist in the United States Navy. They were the only foreigners allowed to join the service without having first moved to the United States.

ED: The program was highly selective, nearly 100,000 young men applied every year. But in some years, as few as just 400 were chosen. By the time the agreement ended in 1992, some 35,000 Filipinos had won a coveted spot in the United States Navy. One of them was Artemio Manalang, who enlisted in 1975. I sat down with Artemio and his daughter, Aprilfaye Manalang. She’s a professor at Norfolk State University. And she studies the experiences of Filipino veterans like her father. I asked Artemio, or Art, as he prefers to be called, what made him want to enlist in the US Navy?

ARTEMIO MANALANG: They were offering good pay. In the Philippines, during that time, was like there are almost no jobs existing. If there are, they’re not really paying you enough to support the family.

ED: I see. How big was your family, Art?

ARTEMIO MANALANG: It’s very big, I’m the second oldest. We’re 11. Yeah, so, I said I have to do something here.

ED: Now what did your family think when you sailed off with the Navy?

ARTEMIO MANALANG: They love it too, because I kept sending money every month. So I can help the siblings and my parents.

ED: So they were proud of you and grateful too, right?

ARTEMIO MANALANG: Yes, of course, yes. The best thing that ever happened to us, it’s like winning a jackpot for life, I think.

ED: Well, that’s great. I don’t want to focus on negative things in such a positive story, but I’m guessing everything wasn’t as they say smooth sailing was it?

ARTEMIO MANALANG: The real struggle was when you’re dealing with sudden change of the environment, because coming from a tropical country like the Philippines, like between 90 degrees, 100 something all year round. And then suddenly, they brought you in San Diego, preferably Treasure Island, where it’s windy and so cold. We were like wait a minute, it’s so cold. It’s so cold, we can’t bear it. So it’s a good thing they gave us our uniforms. So everybody was in their big coats and raincoats.

ED: And it’s just a good thing they didn’t ship you to Seattle, right?

ARTEMIO MANALANG: Yes. And dealing with the people, and then the language, it was a culture shock.

ED: So did you ever run into prejudice?

ARTEMIO MANALANG: Yes. You can feel it sometimes. They say it, but you have to keep thinking forward.

ED: Right, right.

ARTEMIO MANALANG: You have to reset your attitude to where you want to make believe yourself that I’m also as equal as they are.

ED: So can you give us an example?

ARTEMIO MANALANG: Well, the only resentment that I can recall back then was my first few years. You know? Because I was the only– like at my first assignment, I was the only Filipino in the group. Sometimes they would say, hey take them up there where he belongs. I found out later that where I supposed to be belonging to work was up there in the galley.

ED: So do you mean they thought you should have been a cook?

ARTEMIO MANALANG: Yes, because most of my friends, Filipinos who were working as tours back then and cooks.

ED: Right, right. So what work did you do?

ARTEMIO MANALANG: I did maintaining, operating, and troubleshooting propulsion engines. I was in engineering, anyway. I was an engine man to be exact.

ED: Well, that sounds like a lot of responsibility. Were there other Filipino sailors with you? Or were you kind of on your own?

ARTEMIO MANALANG: If I can recall, we were 14, but I was the only one in engineering.

ED: So I guess you were in higher status, but maybe a lonelier position than the Filipino men working altogether?

ARTEMIO MANALANG: Yes.

ED: When you signed up with the Navy, was American citizenship something that was on your mind? Was that a goal?

ARTEMIO MANALANG: Yes, it’s becoming to be a goal as soon as I reported to the ship, because that’s when the Filipinos gather and talk. Every chance we get, hey, how are we going to do this? How are we going to bring our families, how we’re going to improve their lives, our lives? That’s when we found out hey, citizenship. Get them over here, get them enrolled, get them a vocation, college degree whatever, so that when you bring them over here, they’re ready to work.

ED: How long did it take you to achieve that?

ARTEMIO MANALANG: 9 and 1/2 years.

ED: So April, I know that you’ve been looking at the experience of people such as your father in your work. Could you tell us a little bit about what you found from a more analytical perspective?

APRILFAYE MANALANG: Yes. Filipino-American military servicemen and their families, they feel that opportunity and the ability to obtain American citizenship is what they call a blessing from God.

ED: That’s a pretty strong endorsement.

APRILFAYE MANALANG: It is. And it took me off guard. So I then began to ask the question of if they feel that their American citizenship is a blessing, then how do they conceptualize that civically? Because another accompanying finding that has persisted throughout the interviews is just this feeling of what they have termed and coined as [NON-ENGLISH], which means feel indebtedness for the host nation which provided those opportunities as embodied by my father.

ED: So what do you make of your father’s experience and relationship to the larger American experience with the Philippines, which has not always been an easy one.

APRILFAYE MANALANG: I’ll personally share that I feel ambivalent about it, because I know that there is that former colonial relationship. And so there is that aspect of the power dynamics coming to play. And when I interview these military servicemen, that is not the story they’re telling me, by and large. And so, there is the very real interviews in which people are reporting overall a positive experience, and then what I’ve also found in the interviews is that because they feel that blessing of American citizenship, and due to that indebtedness, the first generation, in particular, feels uncomfortable with politically engaging political protests.

ED: I see, it feels like it’s demanding something rather than giving something.

APRILFAYE MANALANG: Right. So I have even heard the phrase of we don’t want to bite the hand that feeds us, and it is enough for them that their children are more successful than they are. What they do say though, is that our children will do that, because our children will not have that indebtedness. I did ask my youngest brother Paul once, do you feel indebted? And he’s like what are you talking about, for what? And I said for being American? And he just goes, you’re weird. I do suspect that might embody my generation.

ED: Well, the possible interpretation of this is you feel the debt has been paid. Your parents paid the debt, and now you’re full Americans to do whatever you want to do.

APRILFAYE MANALANG: What I will say is I am very grateful for the opportunities and blessings that I have experienced due to my father’s enlistment, which I know for a fact would not be possible without his hard work.

ED: So Art, it seems only fitting that you should have the last word. You’ve served the United States a lot longer than most people who were born here. Would you like to reflect on what the story of your life as American sailor means?

ARTEMIO MANALANG: Being an American sailor is to come here and serve the United States Navy and fulfill their dreams that everybody dream about in the Philippines. It was an honor, and it was a blessing from God.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

ED: Artemio Manalang retired from the US Navy in 1999 after 24 years of service. Aprilfaye Manalang is a professor at Norfolk State University.

JOANNE: OK, so Ed, Brian, during the Revolutionary period, you had a whole bunch of different ways to get people to enlist. You had the hiring of mercenaries, you had people being enticed with the offer of money. But one thing we really haven’t talked about is the draft.

ED: Yeah, Joanne, in the revolution you had conscription, but in the Civil War, they took it to a whole other level. Both the United States and the Confederacy had to build vast armies virtually overnight. And the number of men actually drafted was relatively small, because just the presence, the threat of the draft, encouraged men to volunteer before they had to be drafted. If you were drafted, you had to go wherever they sent you. If you volunteered, you could fight with your local unit. And once you were actually enlisted in the Army, North or South, if you were known as a draftee, what they called a conscript, you were not treated well by your fellow soldiers. They considered you somewhat cowardly, and probably pretty inept. They weren’t really thrilled to see you show up on their flank. So it was a stigma attached both at home and on the battlefield, and yet the draft was very important to both sides.

Now it goes away after the end of the Civil War, United States doesn’t have to fight another major war for generations. And so I know that in the 20th century, Brian, they had to scramble when it comes to World War I, right?

BRIAN: That’s right, Ed. In fact, every major war that the United States fought in the 20th century was staffed, in part, by drafting Americans. World War I, the United States got into the Great War very late in the game. So they didn’t have to draft that many people, and a lot of Americans hoped to get back to the draft being an exception, like it was with the Civil War. But World War II comes along, and there are a huge number of Americans drafted. It actually made the Army very egalitarian. Everybody was subject to the draft.

In Korea, the draft continued. It continued through Vietnam, and we really didn’t end the draft until the 1970s when Richard Nixon advocated for what became known as the all volunteer army.

ED: So, Brian, now we’ve gone to an all volunteer army, what would you reckon is the pros and cons of that?

BRIAN: Well, as much as the draft challenges our conception of liberty, for instance, the draft during World War II, for instance, affected all Americans. And the army was a real cross section, to the extent you can get that in an army, of all Americans. You contrast that to the Vietnam War, where there was a draft, but increasingly that draft fell disproportionately on poor people and disproportionately on African-Americans. In order to fight a very unpopular war, a war that was seen as immoral.

ED: So Brian, where does that leave us today?

BRIAN: It’s very easy to forget that when America fights its wars, and we are at war in a number of places, the burden of war is falling disproportionately on those who enlist, those in the military, and it’s not spread fully across a side.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

JOANNE: That’s going to do it for today. But you could keep the conversation going online. Let us know what you thought of the episode or ask us your questions about American History. You’ll find us at BackStoryRadio.org, or send an email to BackStory@Virginia.edu. We’re also on Facebook, Tumblr, and Twitter at BackStoryRadio. And if you like the show, feel free to review it in Apple podcasts. Whatever you do, don’t be a stranger.

MALE SPEAKER: This episode was produced by Andrew Parsons, Bridgid McCarthy, Nina Earnest, Emily Gadek, and Ramona Martinez. Jamal Millner is our technical director, Diana Williams is our digital editor, and Joey Thompson is our researcher. Our theme song was written by Nick Thorburn. Other music in our show came from Podington Bear, Ketsa, and Jahzzar. And thanks to the Johns Hopkins University’s Studio in Baltimore.

ED: BackStory is produced at the Virginia Foundation for the Humanities. We’re a proud member of the Panoply Podcast Network. Major support is provided by an anonymous donor, the National Endowment for the Humanities, the Provost’s Office at the University of Virginia, the Joseph and Robert Cornell Memorial Foundation, and The Arthur Vining Davis Foundation.

FEMALE SPEAKER: Brian Balogh is professor of history at the University of Virginia, and the Dorothy Compton professor at the Miller Center of Public Affairs. Ed Ayers is professor of the humanities and President Emeritus at the University of Richmond. Joanne Freeman is professor of history and American studies at Yale University. Nathan Connolly is the Herbert Baxter Adams associate professor of history at the Johns Hopkins University. BackStory was created by Andrew Wyndham for the Virginia Foundation for the Humanities.

[MUSIC PLAYING]